Low-Stress Buffalo Handling

The calming of American Bison

by Francie M. Berg

We’ve reported stories to you in this space about the early days of hard-riding buffalo wranglers running half-wild buffalo. Some amusing. Some tragic.

Often, early cowboys rounded-up and stampeded buffalo into makeshift corrals and loaded them into boxcars in some of the roughest ways possible, even dragging them at the end of several ropes.

At the time, it seemed to men who were used to working cattle like the only way to get the job done was to run the buffalo hard and stay ahead of them.

Hard-riding cowboys in the early days tried to chase buffalo as they did cattle. In this early 1900’s photo Michel Pablo’s wranglers tried to outrun the buffalo, with mixed results. Today’s buffalo ranchers understand that low-stress livestock handling is far more successful than the tough old cowboy techniques. Montana Historical Society.

I know this has been painful for some of our readers. You visualized all too clearly how violently the wild buffalo were sometimes treated. You mourned that some buffalo in their extreme panic simply died a sudden death.

Buffalo are powerful animals and it was also dangerous for the people handling them. Many riders and horses have been injured or even killed.

In the early days of buffalo ranching, hard-riding cowboys expected these half-wild animals to respond like the cattle that they are not.

When they didn’t, they probably shouted louder, swung their ropes higher and ran the animals harder.

I think you’ll be happy to know that today buffalo are not handled that way.

With buffalo, owners have learned to do the job the buffalo’s way—or get little or nothing accomplished.

As Tim Frasier, buffalo consultant, says, “Bison producers, by and large, are extremely conscious of humane protocol because the species dictates that the producer work with them.”

Ranchers and buffalo managers have learned that buffalo are like wild animals—subject to flight or fight reactions when startled or pushed too hard.

In important ways they are still the undomesticated wild animals they’ve always been. They need to be handled more delicately than cattle.

Imagine Handling Wild Deer

Think about chasing wild deer. How would you go about chasing a herd of 3 or 4 mule deer through a gate out of an alfalfa field?

We certainly wouldn’t use the old-style cowboy tactics—just running them hard toward the gate—would we?

I think our goal instinctively would be to not crowd them—stay back. To move quietly, so as not to alarm them. Allow them time to decide how to respond.

Knowing that if we rush them, some of the deer are going to lunge for the fence—over or under, or slam bang into it.

I’m no expert, but have done considerable reading on the topic, as well as trailed a lot of cows, four days to and from their distant summer ranges.

So let’s go to the experts to learn how to keep buffalo stress levels low.

Instead of running at the deer, it would make sense to hang back and give them time to decide. Maybe then they’d take the easy way—and just trot out through the open gate.

Low Stress Handling

The most important trait for the buffalo handler is calmness, experts say. Establish yourself at the top of the pecking order in a calm and confident way.

For the new buffalo owner or herd manager, whether of a small or large herd, there’s plenty to learn in raising these amazing, magnificent animals.

The modern way of handling buffalo fascinates new owners and old hands alike. With roots in “horse-whispering” techniques, it’s called low-stress livestock handling.

The goal is to develop a calm herd, with the animals content and unafraid.

Buffalo may seem docile, but Grandin says to watch for signs of fear. The goal is to develop a calm herd, with the buffalo content and unafraid, trusting their handlers. NPS.

Fearful buffalo cause great risk both to themselves and humans, warns Dr. Temple Grandin, a well-known expert on animal behavior in the Department of Animal Sciences at Colorado State University, Ft Collins.

She’s a scientist who understands autism and applies some of the related philosophy in her work.

Dr. Temple Grandin, well-known expert on animal behavior in the Department of Animal Sciences at Colorado State University, Ft Collins, uses her experience with autism in understanding fear and stress in working livestock. CSU.

As wild animals, she explains, buffalo are always on the alert for danger, and ready to respond with fight or flight. When alarmed, fear shoots adrenaline through their system and they are ready to react.

People who work with buffalo need to watch for signals of fear, Grandin says. The first subtle signs are licking, blinking, huddling, a raised tail, circular movement—milling—backing up and balking.

As fear and panic increase, so do signs such as hard breathing, frothing at the mouth, vocalizing, bulging eyes, running, pushing, goring, attacking, sitting, jumping or scrambling free of their enclosure.

The last stage of fear is immobility, lying down without responding to stimuli or prodding.

Paying close attention to these signals and responding appropriately teaches buffalo what behavior is wanted. Then they need the opportunity to do it willingly, Grandin says.

The key to helping buffalo understand this is skilled use of their comfort or flight zone, according to Mark Kossler, manager of the Vermejo Park Ranch, New Mexico, writing in the most recent Bison Producers’ Handbook, published by the National Bison Association.

“The gentle dance of us applying pressure, the animal moving away from the pressure and us releasing the pressure, is the main method of getting our animals to move for us in a low stress manner,” Kossler tells buffalo ranchers.

“This sets up a positive cause and effect relationship. That is, we get into their flight zone putting pressure on them, and they, by moving away from us get released from the pressure.”

The flight zone is the personal space of a buffalo and may differ somewhat for each animal.

An alarm goes off in its brain when someone enters that personal space. The optimal handler position is at the boundary of that zone. This allows him or her to manipulate the animal in a low stress manner.

In moving buffalo, another sensitive place is the balance point at their shoulder.

Movement behind the shoulder causes the animal to go forward. Ahead of that point and it typically moves back.

What causes high stress, Kossler warns, is “putting pressure on them and never releasing it. Or worse, no matter what they do, continually increasing the pressure.”

Too much pressure and the buffalo panics. If unable to escape, he will fight ferociously.

Low stress means handlers work quietly and smoothly.

Former cattlemen have learned what not to do with their buffalo: stop yelling, moving fast or erratically, following a rushed schedule, or “forcing” the buffalo. Instead, they give them time to think it over and respond calmly.

Grandin recommends that the crowding pen should never be filled more than 1/3 full at any given time. By providing sufficient room, the bison are able to maintain their dominant order relative to one another. This reduces stress and intra-herd conflicts.

“When bison are tightly confined with other bison, their fear manifests as aggression in the form of goring and pushing those around them. Bison that are to be held in close proximity to other bison should be held with similar bison of the same age and gender.”

On the other hand, buffalo are herd animals and fear being alone in a pen.

A page from the Alberta 4-H Leaders Bison Guide makes a clear point: As a herd animal the buffalo fears being alone.

Grandin also points out, “The first experience an animal has in a new situation is the foundation for subsequent behaviors in similar situations. If the first time a bison enters a squeeze chute—bad things happen to him, he will be reluctant to re-enter.”

“But if the first few times he enters, the experience is neutral or positive, he will be more inclined to reenter the chute.

Only one buffalo at a time in the chute leading up to the headgate avoids pileups. Then work bison quietly and release them quickly, say experts. Parks Canada.

“Likewise, if the last experience the animal has just prior to leaving a facility is positive, such as receiving a highly palatable food reward, the animal will be more receptive to being worked the next time.”

If the handler tries to get buffalo to move by electric shock, yelling, or arm waving, which are all at the extreme end of the pressure gradient, warns Grandin, the bison will immediately become fearful. This fear results in a traumatic experience for the bison and often the handler.

Because of their ability to hear higher and lower frequencies than humans, she suggests that subtle sounds are often effective to move animals forward. The best are novel noises; a rustling newspaper or plastic bag, snapping of the fingers, pennies in an aluminum can, or a shh, shh sound.

Livestock handlers have learned a lot from Grandin, says Clint Peck, Director, Beef Quality Assurance at Montana State University, Bozeman.

“There’s not a rancher in this country that isn’t aware of her work. We have all been influenced by Temple. There is no question her work has helped us all understand more about our animals and how to handle them in a caring and humane manner.”

Because of her work and her perseverance, the beef industry looks very different today than it did 30 years ago, says Peck.

Buffalo handlers are especially following the Grandin techniques today, because they understand that her methods work far better than the tough old cowboy ways of forcing the buffalo.

Temple Grandin has researched, written extensively and developed workshops, teaching her low-stress methods to livestock handlers for more than 30 years. CSU.

Mark Kossler, manager of the Vermejo Park Ranch, New Mexico, writing in the Bison Producers’ Handbook, published by the National Bison Association, warns that “Handling problems may have more to do with how people approach and try to control them than with the livestock themselves.

“Could it be that we are the root problem with poor handling and performing livestock?”

“Low-stress livestock handling should create an environment, in facilities and handling methods that keep animals mentally calm, content and unafraid,” he suggests.

Its essence is handling buffalo in such a way that suits them and keeps them “mentally intact.”

Low-stress methods keep them from becoming “mentally fractured”—which results in wild, erratic and often aggressive behavior.

This involves, he writes, developing an environment on the ranch that “responds to what the animals show us they need.”

Buffalo are continually communicating with us by what they do or don’t do, but are we listening? he asks.

“Do we manage and handle our animals in such a way that we minimize the stress they experience or do we manage and handle our animals in a way that increases their stress?”

Stress occurs, he says, when we place demands on buffalo that they can’t calmly meet or respond to naturally. “This has undesirable consequences that include poor animal performance, aggressive behavior, death loss, injuries, increased disease and health problems, increased handler stress and economic loss.”

Buffalo people know it’s important to keep a watchful eye on the buffalo and respond to their actions in helpful ways.

Dave Carter, long-time director of the National Bison Association, who runs his own buffalo herd, puts it this way, “Through the years, these magnificent animals have taught us a lot.

“Every day spent with bison will provide great insight and understanding.”

The goal is to develop a calm herd, with the buffalo content and unafraid, trusting their owners and understanding their signals and movements.

This is accomplished by establishing yourself at the top of the pecking order in a calm and confident way, being relaxed and consistent—never pushing too hard.

Patricia F. Lee, Lee Buffalo Farms, BSU of Ill, Attica, Indiana, says generally buffalo are quite docile but can change in an instant. They may appear to be sluggish, but are really extremely active.

They can outrun and outmaneuver a horse. They can jump a standard woven wire fence with 2 barbed wires on top from a complete stand still. And they can charge through most any fence and tear it down, if they really want to.

Buffalo today are in a semi-domesticated process, but still cannot be fully trusted, says Lee.

They retain all their natural instincts for survival—and when crowded panic into a “fight or flight” response.

Owners say a buffalo bull can turn in an instant, outmaneuver a horse, jump a woven wire fence with 2 barbed wires on top from a complete stand still or charge through a tight-looking fence and smash it down.

Livestock handlers have learned a lot from Grandin, says Clint Peck, Director, Beef Quality Assurance at Montana State University, Bozeman in 2011.

Dr. Grandin has spent her career looking at the beef industry through the eyes of a cow. She has laid down in muddy corrals, crawled through metal chutes, and even stood in the stun boxes where factory workers deliver their fatal blows.

“There is no question her work has helped us all understand more about our animals and how to handle them in a caring and humane manner,” writes Peck.

Her methods have become even more important in the Bison industry, in which she notes that the problems in handling these “large, skittish animals . . .range from stampeding to intra-herd aggression to ‘suicide.’”

Her studies, she writes, have “focused on bison behavior during handling in squeeze chutes, alleys, holding pens and trucks.”

Kossler lists 8 foundational principles to work on to develop one’s buffalo ranch into a low-stress operation.

Realize that it is our fault, not theirs, if our livestock live in a high stress environment. We need to change how we operate to affect a better outcome for them. Our attitudes towards our animals and philosophies of animal management will have to change, as they are just operating the best they can in the environment we provide for them.

Consistently use signals that livestock can respond to naturally so they can understand our meaning or what we want them to do. Get consistent in how we move our bison in the pasture, from pasture to pasture or in the corral. Realize that if they become unsettled or emotionally fractured, it is caused by something we did. Analyze the feedback we are getting from our stock–this is how they are communicating with us. If we are not getting the desired feedback, then we are the problem and need to change what we are doing.

Apply only the amount of pressure needed to get the desired response, not an ounce more!

Stop “forcing” our bison to do what we want. Replace force with consistent sound handling principles that allow them to learn what we want and gives them opportunity to do it willingly.

Stop doing things that cause immediate “high stress” in our bison such as yelling; moving fast and erratically; not giving them time to think, analyze and respond. Or putting continued unrelenting pressure on them with no release.

Stop having a definite schedule when working with our bison. We need to realize that our “schedule” puts pressure on us that is often transferred to our bison, which causes its own problems. In working with animals, not every day is the same and how we approach it often affects the outcome. If we are on edge and in a hurry, the animals will pick up on this and react accordingly.

Start thinking from the bison’s point of view—getting on the “other side of the horns.” Spend time thinking about what we do with our bison and how it may look or feel from their perspective. If we can get inside them and see what we do through their eyes, it well may change how we do things.

If one approach does not work, even if it did yesterday, try another. Conditions are constantly changing and we need to account for that with our method and approach. Be flexible in what we do and how we do it.

He suggests that learning the techniques will take some reading, research, and lessons from those who know how to do it.

When buffalo feel too confined they often become “mentally fractured”—which can result in wild, erratic and aggressive behavior. National Bison Association.

Curved alleyways and pens with solid sides offer bison the illusion of escape ahead without the risk of being caught in a corner. Alberta 4-H Manual.

Grandin corrals offer detailed plans on easy movement of the animals, through a smoothly working system.

Dr. Grandin makes the point that an increasing awareness of animal welfare and rights issues means that routine procedures that were considered adequate in the past are no longer acceptable in today’s society.

Thus, it is especially important that zoos, parks and other conservation systems have healthy, vibrant bison herds for public education and enjoyment and that they are treated well.

She writes, “A favorable public perception of captive animals is critical to park funding and reputation.

“Calm, beautiful, picture perfect animals are powerful advertisements for parks.”

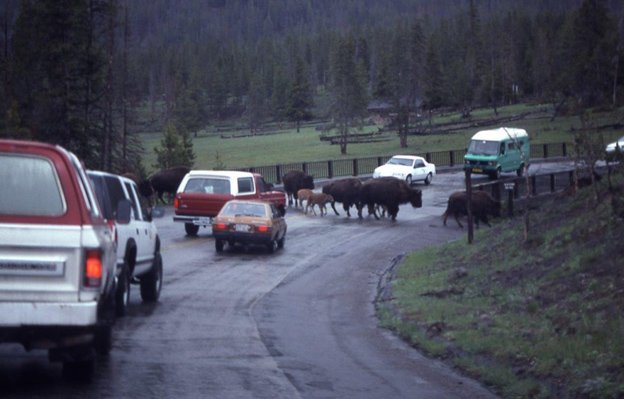

Drivers wise in the ways of wildlife parks and refuges allow buffalo to cross highways when and where they choose in parks, without interference. NPS.

Therefore, she urges that calm, knowledgeable, low stress handling techniques are essential.

Low Stress handling also implies an appropriate set-up of corrals and chutes.

Following Dr. Grandin’s advice and research, owners round corral corners and build solid walls so buffalo don’t spook at distractions or attempt an escape back to the hills.

Resources for Low-stress

Buffalo Handling

Bud Williams Schools. www.stockmanship.com; Excellent videos on Low-Stress Handling. No longer provide workshops.

Cote, Steve. Stockmanship: A Powerful Tool for Grazing Lands Management. Natural Resources Conservation Service; Arco, Idaho. USDA. 2004.

Grandin, Temple. The Calming of American Bison (Bison bison) During Routine Handling. www.grandin.com, written with Jennifer L. Lanier, Department of Animal Sciences, Colorado State University, Ft Collins, CO.

InterTribal Buffalo Council, Resources; for more information, 605-394-9730. Website. itbcbuffalo.com

Kossler, Mark. Low Stress Bison Handling. Bison Producers’ Handbook, National Bison Association. 2010.