Buffalo vs Bison– What Shall We Call Them?

by Francie M. Berg

First published May 5, 2020

What shall we call this magnificent monarch of the Plains—buffalo or bison?

Some people are adamant: the term buffalo correctly refers only to water buffalo in South Asia and Cape buffalo in Africa. We are simply wrong, misinformed, or ignorant to even think of calling the American bison—Buffalo.

Amy Tikkanen, writing in the Encyclopedia Britannica lays it all out. In her world it comes down to “Home, Hump and Horns.” Bison have one set, and buffalo the other.

But not so fast.

Many people who know the science simply prefer the term buffalo. I think most of us in the west—where the buffalo still roam in rather large numbers—do prefer it.

It rolls off the tongue in a friendlier way.

Yes, in scientific usage we agree, it is bison—as is bovine, equine and canine.

My husband Bert, a veterinarian, often used those terms when explaining treatments.

But do we call the cow, horse or dog those scientific names—bovine, equine and canine—in everyday talk?

One happy dog—or is he a friendly canine? Photo by Eric Ward.

Of course not. We don’t even think of them, our beloved friends, that way, do we?

Historic use of Buffalo in America

The word Buffalo actually came from early French fur traders and trappers who called the animals les boeufs, a Greek word for “the beeves” meaning oxen or bullocks.

In that context both names, bison and buffalo, have a similar meaning.

Buffalo has a long history of being used in North America, dating from 1625 when first recorded—even before bison was first documented, in 1774.

Buffalo even has a verb form—to buffalo, meaning to overawe or bewilder.

Here in the west we are well aware that a number of our other species were misnamed by early visitors.

Like buffalo, these early names often stuck, and have become generally accepted into our language, even though they may not derive from their proper scientific origins.

For instance, our antelope is really a pronghorn. An American jackrabbit is a hare, not a rabbit.

Our elk is really a wapiti, while our moose is the same as the European elk. And American caribou are identical to domesticated reindeer in Europe and Siberia.

But that’s okay—we like it this way.

The American Bison Association has made attempts to persuade buffalo ranchers to call their livestock bison. It does seem to work well when ranchers sell meat.

Maybe we all need a bit of distance for that.

That’s not the issue.

Otherwise, calling them Bison seems to put these magnificent, iconic animals out there at some distance. There’s no heart in it.

In contrast, Buffalo seems a good, solid, friendly yet respectful name, with no formality separating us from these majestic animals.

You can put some love into it if you choose.

“Give me a home where the Buff-a-low roam, where the deer and the antelope play.”

“Buffalo gals gonna come out tonite–come out tonite–and dance by the light of the moon!”

Can’t do that with Bison.

That’s not really the issue, though.

“Oh, give me a home where the buffalo roam,” a song for all ages. Photo by Akshar Dave.

“Buffalo gals gonna come out tonite–come out tonite–and dance by the light of the moon!”

Can’t do that with Bison.

That’s not really the issue, though.

Confusion of ‘Home, Hump and Horns?’

I think we can all agree that the Encyclopedia Britannica item as written by Amy Tikkanen, sets the argument out scientifically and clearly. No wiggle room there.

“It’s easy to understand why people confuse bison and buffalo,” Tikkanen writes. “Both are large, horned, oxlike animals of the Bovidae family. There are two kinds of bison, the American bison and the European bison, and two forms of buffalo, water buffalo and Cape buffalo.

Water Buffalo live in South Asia. They tend to have large horns—with wide graceful curves—no hump. Photo by Lewie Embling.

“However, it’s not difficult to distinguish between them, especially if you focus on the three H’s: home, hump, and horns.

“Contrary to the song ‘Home on the Range,’ buffalo do not roam in the American West. Instead, they are indigenous to South Asia (water buffalo) and Africa (Cape buffalo), while bison are found in North America and parts of Europe.

“Another major difference is the presence of a hump. Bison have one at the shoulders while buffalo don’t. The hump allows the bison’s head to function as a plow, sweeping away drifts of snow in the winter.

“The next telltale sign concerns the horns. Buffalo tend to have large horns—some have reached more than 6 feet (1.8 meters)—with very pronounced arcs. The horns of bison, however, are much shorter and sharper.

“Despite being a misnomer—one often attributed to confused explorers—buffalo remains commonly used when referring to American bison, thus adding to the confusion.”

Of course, Britannica is British, lecturing us a bit on our use of the English language. That’s okay, we can take it.

Confusion is not really the issue either. Neither is science—we understand and accept that.

The thing is, we just like the buffalo. And we like to call them that. It fits.

A ‘Harmless Custom’

William T. Hornaday, that great historian of the species, was good-humored about it. He called the animals, Bison in his own writings. Nevertheless, he wrote in 1889:

“The fact that more than 60 million people in this country unite in calling him a buffalo, and know him by no other name, renders it quite unnecessary to apologize for following a harmless custom which has now become so universal—that all the naturalists in the world could not change it if they would!”

Professor Dale F Lott, University of California scientist, puts it even better, I think. He’s not confused about anything– most especially his beloved buffalo!

Born on Montana’s National Bison Range, where his grandfather was Superintendent, he grew up seeing buffalo on the hills every day. His father, from a nearby ranch, worked on the Bison Range—and had married the boss’s daughter.

Professor Lott, who in my opinion surely loved and understood the buffalo as much, if not more, than any other scientist who wrote of them, explains why he uses both terms interchangeably.

“I’ve given a lot of thought to whether I should call my protagonist bison or buffalo,” he explains in the preface to his book: American Bison: A Natural History.

“I decided to use both names.

“My scientist side is drawn to bison. It is scientifically correct and places the animal precisely among the world’s mammals.

“Yet the side of me that grew up American is drawn to buffalo—the name by which most Americans have long known it.

Buffalo honors its long, intense and dramatic relationship with the peoples of North America.”

Lott leaves the discussion there. Enough said.

Ervin Carlson, former Director of the Blackfeet Buffalo Program on the Blackfeet reservation in Northwestern Montana, and past President of the Intertribal Buffalo Council, has put some thought into this issue, too.

He says his people do not call thes animals Bison.

“We think of Bison as a white man’s term.

Ervin Carlson, former president of the InterTribal Buffalo Council, which assists tribes in returning buffalo to Indian country, surveys a new herd released on Cherokee Tribal land in northeast Oklahoma on Oct. 9, 2014. The buffalo were brought from South Dakota by cattle truck. Photo by Jim Beckel, The Oklahoman.

“They were everything to us—we survived on them.”

And when the buffalo suddenly vanished, many of the Blackfeet people starved to death. Of course, they have the right to call these beautiful creatures Buffalo!

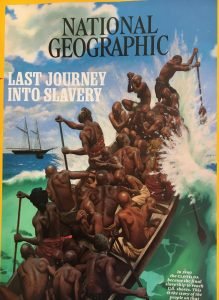

No less an authority than the National Geographic Magazine, which has published many buffalo articles over the years, has declared the terms Bison and Buffalo interchangeable.

In a recent article on the western lands buffalo controversy, National Geographic stated flatly, “Historians estimate there were tens of millions of bison—the term is interchangeable with buffalo—when Lewis and fellow explorer William Clark traversed the northern plains.” (Feb.2020, p75)

Buffalo is defined in that magazine’s Style Manual as, “Singular and plural. Acceptable synonym for bison, which is the scientifically correct designation.”

Apparently, this means that it got the green light from the style committee, which had given it a close review.

National Geographic in its Feb 2020 issue–on the controversy of the American Prairie Reserve land purchases in central Montana—declares the terms Buffalo and Bison interchangeable. Photo by F. Berg.

Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary accepts three categories of “buffalo.” Screenshot.)

Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary also accepts both terms, and in one definition defines buffalo as “any of a genus (Bison) of bovids: especially: a large shaggy-maned North American bovid (B. bison) that has short horns and heavy forequarters with a large muscular hump.”

It also defines the term as “the flesh of the buffalo used as food.”Native Americans often prefer to use buffalo names in their own languages when talking with each other, such as the Lakota terms, Tatanka and Pte.

Other people play with the pronunciation a bit.

Fans of the North Dakota State University Bison football team, winner of 16 national championships and having won its past 36 games, the longest streak in FCS history, have their own style of cheering—roaring—with a “Z” sound.

That ”Z” chant resounds throughout football stadiums across the land—as in “Go Bizon.”

These fans even have their own curled 2-finger salute that goes with the chant to denote the precisely curved horns of a prized bison head.

Curled 2-finger salute of North Dakota State Bison fans denotes curved horns of prized bison head. Photo by Mike Stone, OregonLive.

‘Buffalo Honors a Long, Intense Relationship’

So, when it all shakes out, what should we call them? These majestic, magnificent creatures of the Plains and Prairies?

My answer is this—a consensus of those I call experts:

Call them whatever you like, the term with which you are most comfortable—or use both interchangeably.

Maybe Buffalo when you’re with friends—or Bison.

Bison when you’re with scientists—or Buffalo.

Whichever feels right to you. But as Hornaday suggests, don’t apologize.

It’s a mistake for Americans to think we “should” call our own Greatest Mammal whatever others tell us we should.

We can say, cheerfully, with a smile, no trace of rancor, “No, I don’t think so.”

To many of us, they are simply buffalo.

This is the name that honors the majestic animal we know.

Buffalo celebrates that “long, intense and dramatic relationship” they have with the Native people and settlers of North America.

And that’s the issue.